Forget anatomy and take on art

A new perspective on physical balance

DISCLOSURE: At Body Transcendence, we will always give you our honest opinion and only endorse products and services we truly believe in. This post may contain affiliate links, meaning, at no cost to you, we may make a small commission if you decide to make a purchase through our links.

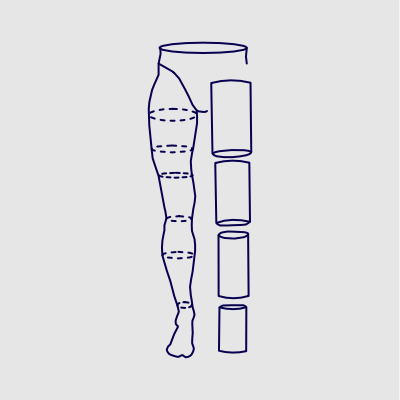

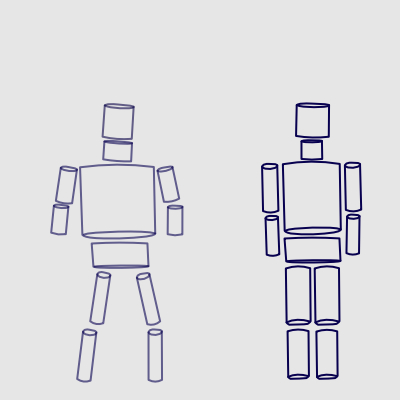

Muscles seem like a necessary part of any discussion about physical balance. But they weren't a big part of my structural integration training. Instead, my teacher introduced us to what he called the cylinder model. It was a way of viewing the body as a collection of cylinder shapes. The arm cylinder connected to the torso cylinder, the neck cylinder connected to the rib cylinders, the calf and thigh cylinders made up the leg cylinder. The spine, the rib cage, the arm, the leg ─ all cylinders.

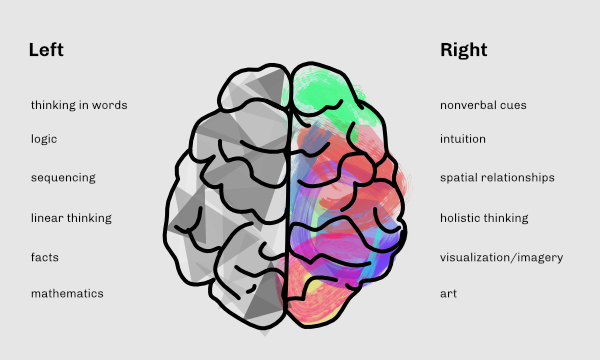

Though I didn’t know it at the time, the cylinder model was developing the right side of my brain ─ I was learning to understand the body holistically. This was in stark contrast to everything I learned in school ─ and life for that matter ─ which was dominated by left-brained, linear thinking. The right-brained perspective is not one that comes naturally to us scientific types, but it is necessary to improve imbalance rather than treat the symptoms it causes.

A balanced body from an artist's perspective

What then, do cylinders have over muscles? The cylinder model teaches us about relationships; the muscle model limits us to the symptomatic parts. Common questions might be, what muscles cause back pain or what muscles should be strengthened to improve ankle stability? Commonly, symptoms like back pain or ankle instability are treated as separate issues. Though the effects of symptom-driven treatments can give some relief, they are often short-lived because they don’t make the part and the whole function better together. Cylinders, on the other hand, show us the big picture. Instead of asking what muscles cause back pain, we ask how each cylinder connects to the next, and the next, and the next. We can then balance the whole system, not just treat the parts.

Cylinders show us relationships, but we can understand those relationships better through art. Line, shape, form, and space are elements of balance used in art. Combined, these elements make the gestalt ─ the organized whole. To get a right-brained perspective on the human whole, let’s look at these elements through the lens of structural integration.

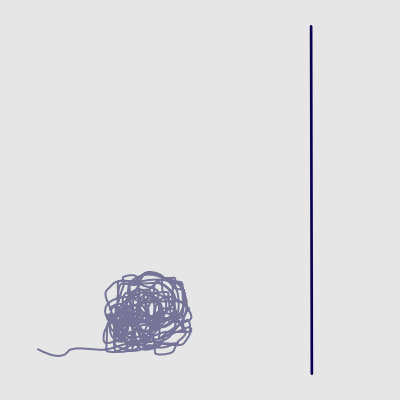

Line

When a body is balanced, it resembles a vertical line. It looks long with stacked joints and connected cylinders. Lack of a line reveals the twists and rotations of imbalance. They are tell-tail signs of compression and disorder that cause pain, tension, and joint immobility. As someone goes through structural integration (SI), their patterns of twists and rotations are unwound through the fascia. As fascial twist is unwound, so are the imbalances of the body. The cylinders and joints become aligned. Compression is removed, and the body lengthens.

Shape and form

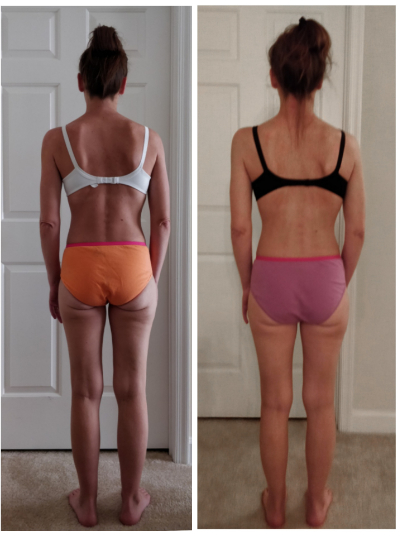

Shape and form are two sides of the same coin. Shape is a two-dimensional concept that involves height and width. Form is three-dimensional and includes volume. While the shape of a balanced body resembles a vertical line, the form resembles a cylinder. When cylinders have good shape and form, their length, width, and volume are proportionate. Together, they look connected rather than disjointed. Fascial twist causes fascia, bone, and muscle to get stuck together in a disordered pattern. That twisted pattern dictates shape and form. The more twist present, the shorter, tighter, and less straight the body looks. Through the SI process, the unwinding of fascial twist restores balanced shape and form.

Space

Space is the most complicated of the elements so here is my best attempt to simplify it. Space can be evaluated two-dimensionally, as in, there is a lack of space between the navel and the hip bone, or three-dimensionally, as in, the space inside the leg cylinder is too small compared to the space inside the torso cylinder. When the body has appropriate space, the cylinders look proportionate in form and shape ─ they are connected. The amount of space within a cylinder is directly correlated to the amount of fascial twist present. Lack of space can look compressed, small, or stocky. Even if the joints appear to be aligned, there can still be a lack of space. In that case, the cylinders look heavy and thick relative to other cylinders. As fascial twist is unwound through SI, space is created inside the body. Space gives each cylinder the freedom to lengthen and each joint the ability to move.

The takeaway

Our left-brain dominance has produced left-brain dominated treatments ─ ones that focus on symptoms rather than balance. When you integrate a holistic, right-brained approach, you get systemic changes that last.

It was cylinders, not muscles, that taught me about physical balance. That back pain isn’t just in the back, and knee pain isn’t just in the knees. Muscles aren’t the only or even the best way to look at balance. Dr. Ida Rolf famously said, “Forget anatomy and take on art. You’ll look at the body as something around a line, a vertical line.” You can learn a lot when you’re open to new perspectives.